Blackouts in the UK: are they increasing?

Here's why blackouts happen, the most common causes, how frequently they're happening in the UK – and what you can do to prepare.

Written byJosh Jackman

Calculate savings

What kind of home do you live in?

Calculate savings

What kind of home do you live in?

UK blackouts: at a glance

📉 The number of blackouts is decreasing in the UK

🔌 Blackouts come from unexpected shifts in electricity supply or demand

❌ Common causes include faulty hardware, extreme weather, and mistakes

⚡ It usually takes two major power plants tripping to start a blackout

💷 The grid uses software and financial rewards to avoid outages

Blackouts, or unplanned power cuts, are inconvenient at best and potentially life-threatening at worst.

In April 2025, Spain and Portugal suffered nationwide blackouts that lasted around 10 hours, as a massive voltage surge stranded tens of thousands on public transport systems, caused car crashes as traffic lights shut down, and left emergency services uncontactable.

This understandably led people in the UK to worry that a similar blackout could happen here. While it’s possible, it’s unlikely.

The government's National Risk Register estimates that there's a 1-5% chance of a national or regional grid failure in the next five years.

It’s still a good idea to become less dependent on the grid, though, for reasons that go beyond power cuts. If you’re wondering how much you could save with a solar & battery system, enter a few details below and we’ll provide an estimate.

What causes a blackout?

It’s common knowledge that a blackout is when you lose power, and most people in the UK have experienced one – but it’s less widely known that blackouts are caused by significant changes in frequency.

Electrical frequency is the number of times per second that an alternating current (AC) moves back and forth. This is what gives AC its name, as it alternates between positive and negative voltage.

In the UK, our AC electricity travels through this cycle 50 times per second, so our frequency is 50 hertz (Hz). Most countries operate on 50Hz, though some – mostly in the Americas – use 60Hz.

All electrical items in the UK are designed to work at 50Hz, and will stop functioning if the frequency spikes or dips more than a little bit. This is tricky, since the frequency changes nearly every second.

When demand rises compared to supply, the frequency ticks upwards, and when the supply increases above demand, the frequency drops.

This is because the nation’s frequency is directly related to how fast its grid-connected generator turbines are spinning.

When demand exceeds supply, energy companies have to increase their output, which on a basic level means making their turbines spin faster. If that’s not enough to get the frequency to its desired level, the grid will delve into its battery storage reserves.

If there isn’t enough stored energy to make up the difference, the only way to find balance is to reduce the supply – which means deliberately cutting off power in selected areas, for a set time. That’s the last resort, so if it doesn’t work, blackouts are inevitable.

Fortunately, most of the process is automated, so problematic shifts in the frequency can generally be fixed within milliseconds.

The publicly owned National Energy System Operator (NESO), which runs Britain’s electricity transmission system, is legally obliged to keep the frequency to within 1% of 50Hz – so between 49.5Hz and 50.5Hz.

As the margins are so fine, NESO has set its own internal target of 0.4% – or 0.2Hz – to be safe.

Blackouts vs selective power cuts

Whereas blackouts are when the grid fails unexpectedly, selective power cuts are planned outages designed to prevent blackouts.

Grid operators normally turn to selective power cuts as a last resort, after exhausting all their options to increase supply.

This gives the operator some time to fix the issue, while reducing the risk that key buildings and infrastructure – like hospitals, schools, and trains – will suddenly suffer a blackout.

Households will generally be told in advance when a power cut is planned, and if possible, they’ll be scheduled for a low-consumption time, like the middle of the night.

Fortunately, the Distribution Network Operators (DNOs) – which run the hardware that supplies each region of the UK with electricity – have put another level of protection in place between selective power cuts and blackouts.

If the level of electricity being supplied to a region drops without notice, the DNO’s system will automatically cut off a small number of recipients, then gradually increase this amount until the risk of a large blackout is nullified. This process is known as load shedding.

Common causes of blackouts in the UK

Blackouts are caused by a significant imbalance between supply and demand.

This is usually the result of power stations unexpectedly tripping – which is when a plant disconnects from the network and therefore stops transmitting electricity.

A trip can be brought about by multiple factors, including faulty equipment, extreme weather, and mistakes by the people running or maintaining the network. When more than a million customers lost power in 2019, all of these causes were involved (more on that below).

Troublesome weather events like flooding, snow, and strong winds typically occur more often in winter, which is why the grid fails more often in this season than any other.

Between 2010 and 2019, wind and gales, lightning strikes, and snow and ice – respectively – caused the most weather-induced power system failures, according to a study by Bristol University and the Met Office.

They were fixed in this order in every season apart from summer, when lightning strikes were responsible for a massive 68% of weather-based outages, and heat from the sun was understandably more of an issue than ice and snow.

One power station tripping isn’t normally enough to cause a blackout though, as NESO has built-in, automatic processes and battery storage that come to the rescue when needed. This is good planning, since large generators often trip.

It generally takes at least two major power stations tripping at the same time, in which case the grid may not have enough reserve power to balance the frequency. This rarely happens.

In some situations, one trip can lead to other stations tripping, as the increased load on other generators becomes too much for them to handle.

This can result in a disastrous chain reaction – but the UK’s grid is well-built enough to make this unlikely.

How frequent are blackouts in the UK?

66% of people in the UK have experienced a power cut at some point in their lives, according to a UKPower survey from 2023 – but they’re still infrequent.

The average UK household is affected by 0.4 outages per year, losing electricity for around 38 minutes per home, according to the latest Ofgem report.

That means you’ll be hit with around four power cuts per decade, which isn’t a lot.

And even when power cuts do happen, they may pass unnoticed, since the DNOs usually schedule them for off-peak times.

Some regions have to endure power cuts more than others though, with homes in North Scotland and south England experiencing around twice as many per year as those in north-west England.

Recent major blackout events in the UK

The tiny margins when it comes to frequency were behind the blackout of 9 August 2019, when lightning took two major power plants offline, producing a sudden drop in frequency.

The failures at a gas plant in Bedfordshire and an offshore wind farm in the North Sea caused a blackout for 1.15 million customers, forced the cancellation of 371 train journeys, and led the plants’ companies to voluntarily pay Ofgem £9 million.

The frequency drop in question? 2.4%. How long was the frequency below 49.5Hz to cause this amount of mayhem? Two minutes and 21 seconds.

For 144 seconds, the frequency fell below the required level, spawning hours of chaos.

This is an extremely unusual situation, however. Two power stations rarely go offline unexpectedly and simultaneously in the UK, which is part of why significant blackouts are so rare here.

Historically, most blackouts have been caused by severe weather, such as the infamous Great Storm of 1987, which felled 15 million trees and left nearly 1.5 million people without power.

Storms generally cause the most damage, as they did in 2013, when two major storms hit in two months. In October, the St Jude storm left a path of destruction from the south west to East Anglia, leaving more than 310,0000 homes in the dark.

Then in December, a series of storms caused blackouts at 100,000 homes in Scotland, and resulted in 50,000 households in south England losing power over Christmas.

And two years later in December 2015, Storm Frank plunged around 49,000 Scottish and Northern Irish homes into darkness.

Flooding can also wreak havoc. In summer 2007, the UK’s most serious floods in 60 years caused 42,000 homes in Gloucester to lose power for up to 24 hours.

How does the grid prevent blackouts?

The grid prevents blackouts with a combination of software, regulations, and financial rewards for cooperative suppliers.

Its main tools are the balancing mechanism, frequency response, the Capacity Market, and the Demand Flexibility Service, all of which we’ll run through below.

The Balancing Mechanism

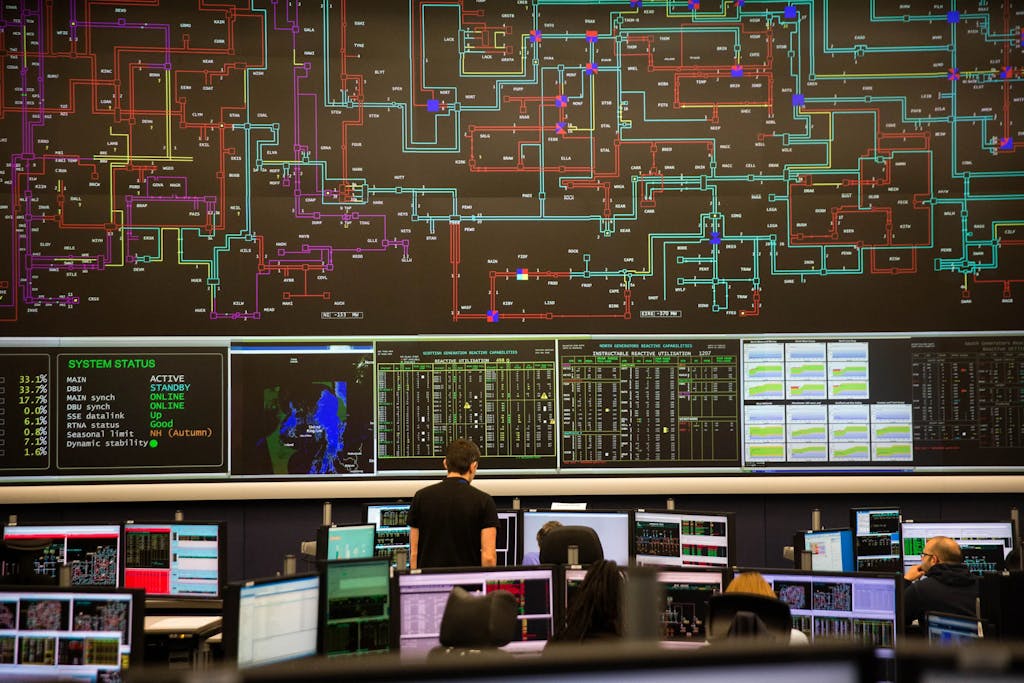

At NESO’s Electricity National Control Centre (ENCC) in Wokingham, experts engage in a neverending, round-the-clock online auction called the Balancing Mechanism, which ensures demand and supply stay level.

Between 60 and 90 minutes before every 30-minute period, electricity generators and suppliers will submit ‘bids’ and ‘offers’ that outline how much they’ll accept to raise or drop their supply or consumption.

The Balancing Mechanism takes this data and calculates how much it’ll cost to provide electricity during that half-hour.

The ENCC’s energy team, which is at the controls, will take into account predictions made by the demand forecasting team – which looks weeks into the future – and the strategy team, which operates on a rolling 24-hour schedule.

These experts will then buy changes in the demand or supply, while trying to be as cost-effective as possible.

The team takes 3,100 actions every day to ensure that the nation’s demand and supply remain relatively level with each other.

Frequency response

In an attempt to ensure the frequency always stays within its required limits, NESO pays some suppliers to be ready to provide less or more electricity.

This takes the form of six response services that energy companies sign up to provide.

All these services can be categorised into one of two types: dynamic and non-dynamic responses.

Dynamic services involve providers adjusting their supply in real time, second by second.

Non-dynamic responses only kick in when the frequency rises or drops beyond a certain point, and require providers to adjust their supply within 10 to 30 seconds, then keep that supply constant for 30 minutes or more.

The Capacity Market

The Capacity Market (CM) involves the grid paying specific generators to produce more electricity or reduce demand when the nation’s supply can’t keep up.

Companies can earn a place on the CM by successfully bidding in auctions that are either one or four years ahead of time.

Many energy companies use a portion of the money they receive through the CM to fund tariffs that incentivise customers to shift their energy consumption – or let the supplier do it – on a daily or occasional basis.

This includes time of use tariffs like Good Energy EV Charge and British Gas Electric Driver, and tariffs where you hand over some control of your electricity consumption, like Intelligent Octopus Flux and Fuse Energy Smart EV.

The Demand Flexibility Service

The Demand Flexibility Service rewards homes and businesses for using less electricity during peak times.

Launched in 2022 during the energy crisis, the scheme involves NESO paying energy companies if they manage to reduce the amount their customers use during peak periods.

This is often – but not always – during the daily 4-7pm peak.

Suppliers achieve this by offering incentives, like money off your energy bill for every kilowatt-hour (kWh) you don’t use, compared to your average consumption.

The likes of British Gas, Octopus, and ScottishPower have signed up to this initiative, and anyone can take part through companies like Uswitch.

To learn more, read our guide to the Demand Flexibility Service.

Are blackouts becoming more common?

Blackouts are becoming less common in the UK.

The average household experiences 43% fewer power cuts now than it did in 2011, and spends 46% less time without electricity.

However, the growth of renewables could reduce inertia, which may be an issue in the coming years.

Inertia is the ability of an object to resist changes to the status quo. In this context, it refers to how closely a grid sticks to its intended frequency when the supply or demand suddenly, dramatically deviates.

Our grid has previously been able to rely on the inertia of spinning turbines, which are common at power stations that use fossil fuels, and keep turning for a while even when their energy source temporarily stops.

Without enough inertia, an incident like a lighting strike can cause the frequency to drop too fast for the grid’s preventative mechanisms to activate, leading to blackouts.

Wind and solar farms don’t have spinning parts that create inertia, which means that as we move to a more renewable-heavy electricity network, we’ll see larger changes in frequency.

Fortunately, there’s a way of avoiding this problem: wind and solar farms can use grid forming technology that creates synthetic inertia. It does this by releasing electricity in a controlled way, instead of just feeding it straight into the network as it’s generated.

This development is still new, and NESO is working to make it easier and more appealing for renewable generators to use the technology – but they need to embrace it to swerve a future with more blackouts.

How can you protect against blackouts?

The best way to protect against a blackout is to have a source of power you can use if the grid goes down.

Unfortunately, most solar & battery systems will automatically disconnect when a blackout hits, so they don’t export to the grid and electrocute any engineers working on the power lines.

You can avoid this scenario by going fully off-grid, or by getting a battery with emergency power supply (EPS) functionality.

This won’t allow your solar panels to generate electricity, but it will enable your battery to supply some of your home with the electricity it has in reserve.

EPS isn’t worth it for most UK households, as it’s expensive, power cuts are generally infrequent, and you’d have to dedicate a substantial percentage of your battery’s capacity to holding emergency power.

It’s an option though, and can be useful if you regularly suffer blackouts or have vital medical equipment that requires a constant source of electricity.

Summary

Blackouts have decreased significantly in recent years, as NESO has worked to improve its network and power cut prevention schemes.

Major blackouts still happen every so often, but they’re usually due to serious weather events, which are harder to guard against.

It’s not usually cost-effective to protect against blackouts with a solar & battery system, and the increasingly renewable-heavy nature of the grid could lead to more power cuts – but the spread of grid forming technology should stop this outcome.

If you’re wondering how much you could save with a solar & battery system, enter a few details below and we’ll provide an estimate.

UK blackouts: FAQs

Has the UK ever had a blackout?

Blackouts, also known as unplanned power cuts, are common in the UK.

Thousands of blackouts occur every year. For example, across 29 and 30 July 2025, UK Power Networks (UKPN) reported 38 unplanned power cuts that affected more than 180 customers.

The company is one of six Distribution Network Operators in the country, so we can assume that the national figures are much higher.

Fortunately, most blackouts in this country are short, with limited consequences.

How long does a blackout usually last in the UK?

Blackouts usually last a few hours at most in the UK, though they can stretch to a day or longer.

This contrasts with power cuts in general, which are usually planned, generally last around 95 minutes, and only happen once every two and a half years on average, according to Ofgem.

Going without power for that long isn’t normally too much of an issue, as long as you don’t have crucial medical equipment.

The food in your fridge should remain safe to eat for four hours, and your freezer should keep its contents frozen for 24 to 48 hours.

Should I prepare for blackouts in the UK?

It’s always worth preparing for blackouts, even though it’s not likely that there’ll be widespread blackouts in the UK any time soon.

Extreme weather events like gales, lightning strikes, and floods can cause blackouts that last days, and their effects can be hard to predict.

Make sure you have a torch and spare batteries, portable battery packs that can charge your phone, as well as entertainment like books, board games, or jigsaws. It’s also worth having a collection of snacks and non-perishable food like tinned meat, vegetables, and fruit.

If you’d need additional support during a blackout, sign up to your energy provider’s Priority Service Register.

Written byJosh Jackman

Josh has written about the rapid rise of home solar for the past six years. His data-driven work has been featured in United Nations and World Health Organisation documents, as well as publications including The Eco Experts, Financial Times, The Independent, The Telegraph, The Times, and The Sun. Josh has also been interviewed as a renewables expert on BBC One’s Rip-Off Britain, ITV1’s Tonight show, and BBC Radio 4 and 5.